WHERE DO WE START?

There is a lot to learn, but you have come to the right place to get more information on climbing basics! Climbing is an incredibly varied activity. Quite a few different and often overlapping specialties fit under the broad umbrella of “climbing.” Climbing can take place on big mountains, small cliffs, or even indoors. It can involve ascending natural or man-made rocks, frozen streams of ice, snow, glaciers, or a combination of these surfaces. It can be as short and accessible as climbing a ten-foot-tall boulder in your backyard or as big and inaccessible as summiting an 8,000-meter high peak half way around the world. Climbing can involve literally tons of specialized gear or no gear at all. All of this begs the question: where do we start?

Let’s begin with a very quick summary of some of the key disciplines of climbing and then go into a bit more depth about the terminology and equipment that you might use at an indoor climbing gym like N3C. There is no way that this page could possibly tell you everything there is to know about climbing, but hopefully, we can at least provide an introduction to the rock climbing basics.

DISCIPLINES OF CLIMBING

As mentioned above, there are different, sometimes overlapping ways to categorize various different kinds of climbing. As with many skills that have evolved and fragmented over time, there is some disagreement even within the climbing community as to the specific definitions of or boundaries between the various climbing disciplines.

TECHNICAL CLIMBING VS. SCRAMBLING

Before going into details on the various ways to categorize climbing, a general concept that is used in climbing is the notion of how “technical” a particular climb is. The more “technical” a climb is, the greater the level of climbing-specific skill that is necessary to ascend it. Non-technical climbing is generally considered to be “scrambling” – which basically means that while you may need to use your hands for balance and to occasionally pull yourself over an obstacle, most people do not see the need for a rope.

ROCK CLIMBING

A broad category that encompasses the ascent of natural or man-made rocks.

ICE CLIMBING

Ascending ice (frozen water) using specialized equipment. Ice climbers hold onto ice axes (or “ice tools”) with sharp metal picks that they swing into the ice. They affix metal spikes, called crampons, to their boots, which they kick into the ice.

MIXED CLIMBING

Ascending a mixture of rock and ice. Mixed climbing involves the use of crampons and ice axes, but also includes ascending rock while still using those tools.

SIZE / HEIGHT OF THE CLIMBING OBJECTIVE

Bouldering

Climbing short routes that do not require the use of a rope. The term comes from the practice of climbing on boulders. This is often considered the purest form of climbing because it focuses on the athletic motion of climbing and uses a minimal amount of gear: no harness, rope, or hardware. You don’t need any specialized gear to boulder, although most boulderers use climbing shoes, chalk to dry their sweaty hands, and a pad to protect their falls. As a side note, bouldering is exploding in popularity faster than any other sort of climbing.

Cragging

A crag is a British term for a small cliff or rock outcropping. Cragging generally means climbing on such cliffs. It has also been expanded to encompass climbing on a relatively small cliff that is easy to get to and, in case of emergency, get off of. Some folks have further expanded the definition of the term to include indoor climbing. Most people would agree that climbing at Rumney is cragging while climbing on Cannon Cliff is not.

Big Wall Climbing

Traditionally, big wall climbing involved very long (1,000 feet or longer) routes, on consistently steep rock, with sustained difficulty (usually requiring aid climbing techniques), and typically requiring haul bags and a portaledge (to spend one or more nights hanging from the wall). Any of the full length routes on Yosemite’s El Capitan count as the epitome of big wall climbing, but some routes on Cannon Cliff are also considered big walls.

Mountaineering

This is the granddaddy of climbing. You look up at a big mountain and you want to get to its top. Mountaineering often involves a mixture of challenges to deal with, including altitude, weather, and remoteness. Historically mountaineering is more focused on getting to the top than it is focused on the technical difficulty of ascending the rock, snow, or ice.

Alpine Climbing

A term that is somewhat similar in meaning to mountaineering, alpine climbing refers to climbing in an alpine environment. Some argue that mountaineering becomes alpine climbing when the technical difficulty of ascent becomes the crux of the route, as opposed to negotiating alpine elements (weather, altitude, etc.).

FREE VS. AID CLIMBING

When most of us think about climbing, we imagine individuals ascending using their own power. This is what climbers call “free climbing.” It is the most common form of climbing. Climbing something free means that the individual did not use anything man-made to help them make forward progress. It has nothing to do with whether or not a rope is involved to catch the climbing should she fall. (Most free climbing involves climbing with a rope to catch a fall!)

Climbers use aid when they cannot (or simply choose not to) climb something free. “Aid climbing” is when a climber uses the assistance of objects to help them ascend: bolts, pitons, the rope itself, or some other form of climbing protection. This type of climbing involves a great deal of specialized gear – including hanging ladders known as “aiders” or “etriers” to stand on while placing the next piece of protection. Aid climbing has its own rating scale from A0 to A5 (or potentially A6) based on the difficulty of placing gear and the ability of the gear to hold a fall. Many routes that were originally aid climbed have subsequently been free climbed.

SOLOING

To climb “solo” means to climb without being attached to another person. There are several types of soloing:

Free soloing is climbing without a rope on a route that most people use a rope when climbing. This is what climbers generally think of when they think of soloing. Some climbers are particularly renowned for their free soloing. Alex Honnold, Dean Potter, Peter Croft, and the late Dean Potter and John Bachar are several such climbers.

Rope soloing is climbing alone using a rope to protect falls. One can top rope solo or lead solo. Either way, rope soloing involves a specialized process of self-belaying while climbing.

Deep water soloing, also known as psicobloc, is a sub-type of free soloing that involves climbing cliffs that overhang water so if the climber falls they land in the water.

Free BASE is a type of free soloing where the only protection is a BASE parachute. The idea is that the climber can turn a fall into a BASE jump off the face of a cliff. This is obviously only attempted by individuals skilled at both climbing and BASE jumping.

ROPED CLIMBING BASICS

Roped climbing usually involves two people: a climber and a belayer. The climber climbs while the belayer controls rope to catch the climber if she falls or wants to be lowered. Belayers feed the rope through a mechanism (creatively called a “belay device”) which is attached to their harness to create a mechanical advantage and make it easy to hold the rope even when the climber’s full weight is on it.

There are two types of roped climbing: top roping and lead climbing.

TOP ROPE CLIMBING BASICS

Climbing on a Top Rope

Top roping is the type of climbing most people are familiar with. With top roping, the rope is already in place going through an anchor at the top of the climb (thus the term “top rope”). The climber ties into the end of a rope closest to the wall and the belayer is attached to the other end of the rope (via their belay device). As the climber ascend the wall, the belayer takes the rope in. If the climber slips, the belayer holds the rope and the climber barely drops at all.

Falling on a Top Rope

Even on a top rope, the rope stretches a bit but the climber shouldn’t fall any distance if the belayer is doing her job (if the wall is overhanging, then the climber will swing out into space). At any point, the climber can hang in the rope to take a rest while the belayer holds their weight. When the climber is ready to come down, the belayer lowers her in a controlled manner.

LEAD CLIMBING BASICS

Climbing on a Lead Climb

Lead climbing is a more advanced type of climbing in which the rope begins on the ground and the lead climber ascends with the rope, clips it through protection that is affixed to the wall as she climbs. Different from top roping, when lead climbing, the belayer lets out rope as the climber ascends (since the rope begins on the ground the belayer has to let rope out as the climber gets farther and farther up the wall).

Falling on a Lead Climb

Another difference between top roping and lead climbing is that lead climbers may well fall quite a distance. Imagine being just 3 feet above your last piece of protection. This means that there is 3 feet of rope between the climber and the last place that the rope is connected to the wall. If the climber falls, she will drop the 3 feet to the last piece of protection and then 3 feet past it (remember that there are 3 feet between the climber and the protection). The rope will also stretch, there’s usually at least a little bit of slack in the system, and the belayer might be lifted off the ground by the impact force of the fall. Therefore, a slip just 3 feet above a piece of protection will probably be a fall of 7 to 10 feet.

AUTO BELAY CLIMBING BASICS

At N3C we have plenty of both top roping and lead climbing. We also have TrueBlue auto belays, which are basically a form of top roping where a mechanical device provides a belay instead of a person. As the climber ascends the wall, the device retracts the line that the climber is attached to. When the climber lets go or falls, the auto belay lowers her at a controlled rate to the ground.

BOULDERING BASICS

Bouldering is a type of climbing that involves short ascents without a rope. Bouldering climbs are called “problems” because they are a relatively short series of moves that need to be solved. These problems are often very acrobatic and quite physical: they might only be 5 moves long, but each move is a huge effort. For this reason, bouldering is often more physically demanding than roped climbing, so it’s not necessarily the best type of climbing for beginners.

CLIMBING BASICS – WITHOUT ROPES

Since there are no ropes in bouldering, every bouldering fall is a ground fall. Thick “bouldering pads” are used to soften the fall when climbing outdoors and indoor gyms cover the bouldering area with thick padding (N3C’s bouldering flooring system 13” thick and has 3 different densities of foam). Even with the padded floor, however, you need to pay attention to how you fall while bouldering and always have a spotter to redirect your fall in case you fall out of control.

DIFFICULTY RATINGS

Climbs have ratings so that we know what we are getting ourselves into before we start the route.

Different rating systems are used for bouldering and roped climbing because the two disciplines are so different. Bouldering is a short sequence of challenging moves while roped routes are longer and often have significantly easier moves and rests interspersed with harder moves. To make matters more confusing, different grading systems have evolved in different parts of the world. Here we present some basic information about the standard difficulty ratings used in the US. Continue reading for the last section of climbing basics.

Roped Climbing:

The Yosemite Decimal System (YDS)

The Yosemite Decimal System (YDS) is the most widely used system for classifying the difficulty of roped climbing in the US. It categorizes terrain according to the techniques and physical difficulties encountered when rock climbing. All of the roped climbs at N3C are rated using this system.

YDS begins with a high level breakdown of the different levels of climbing:

Class 1: Hiking

Class 2: Simple scrambling, with the possible occasional use of the hands. Many trails in the White Mountains include some Class 2 sections.

Class 3: Scrambling where just about everyone uses their hands to some degree; a rope might be carried. Trails such as the Huntington Ravine Trail on Mount Washington involve some Class 3 climbing.

Class 4: Simple climbing, often with exposure. A rope is often used. A fall on Class 4 rock could be fatal. Typically, natural protection can be easily found.

Class 5: Real rock climbing on which most people use a rope to catch a fall. All roped climbs at N3C are considered 5th Class. This is why the rating of all climbs here begins with “5.”

Class 6: Aid climbing where the climber weights gear to ascend.

5th Class Difficulty Breakdown

5th Class routes are further broken down by difficulty. The scale is open ended, beginning with zero and currently going up to fifteen. The rating is usually based on the hardest move of the route, but sometimes is a bit higher if it is sustained at that level. Grades are sometimes further postfixed with “+” (harder) or “-” (easier) or with a letter (“a,” “b,” “c,” or “d”) to further distinguish the difficulty range within a single grade. They are denoted with the class and the difficulty separated by a period: “5.0” for a very easy climb to “5.15d” for what is the hardest climb in the world as of the fall or 2017. When verbalizing grades, just say the numbers separately: a 5.2 is “five two” and a 5.10+ is “five ten plus.”

Here is a rough breakdown of difficulties:

5.0 to 5.6: Straightforward climbs that many beginners will be able to climb on their first try. Usually the holds are relatively large and and the moves are intuitive.

5.7 to 5.9: Intermediate or moderate climbs. The moves start getting tricky and the holds get smaller. A lot of really fun climbs are in this difficulty range.

5.10 to 5.11: Advanced rock climbing. This is where things get really hard. Most “weekend warriors” aspire to this level of climbing.

5.12 on up: Extremely difficult! It generally requires climbing multiple days a week for a long time to get this good. (For reference, there might be half a dozen to a dozen climbers in the world who can climb 5.15.)

Bouldering:

The V Scale

The V scale is the most widely used bouldering rating system in the US. The easiest problems on this scale are rated V0 and the hardest (currently) are V17. Just as with the Yosemite Decimal System for roped climbs, the V scale is open ended so as climbers ascend harder and harder problems, the scale goes higher and higher.

The V scale officially begins with V0 (“vee zero”). Even though these are the easiest official V grades, they are challenging. Each move should be in the 5.9 to 5.10 range. As the numbers go higher, the problems get harder.

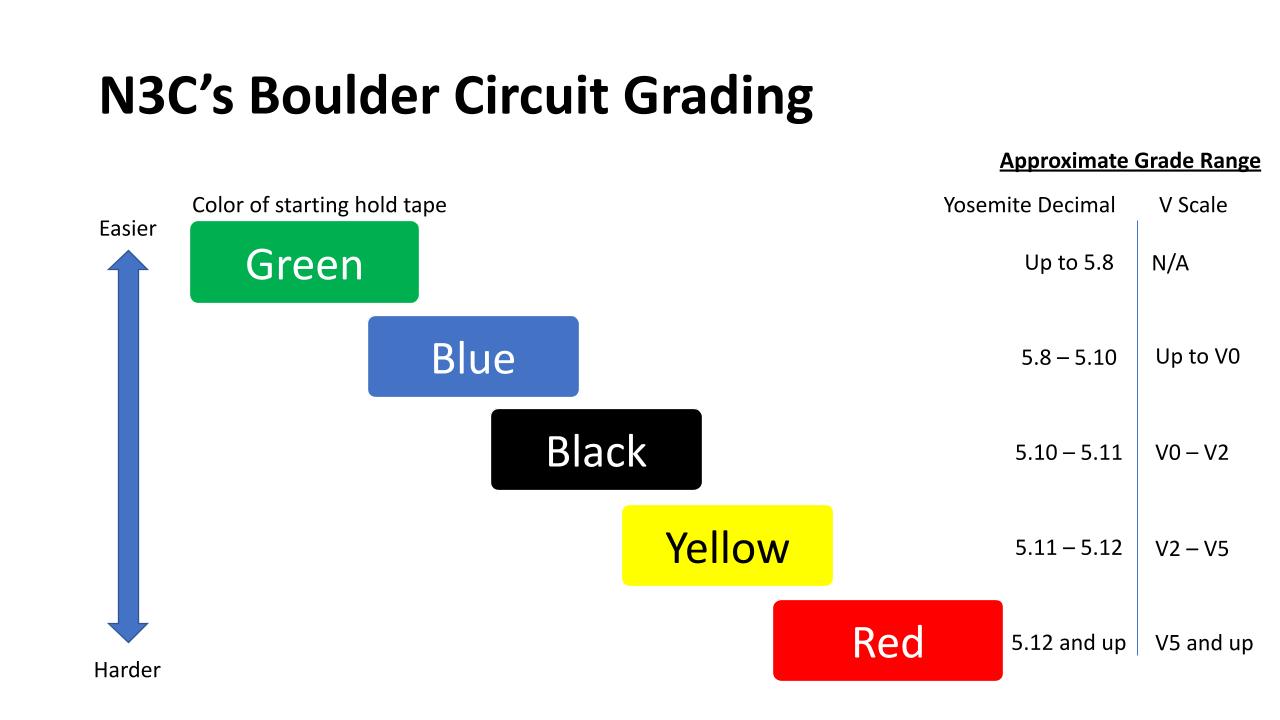

At N3C we use a circut grading system to rate our boulders instead of the V scale. This is because we set many boulder problems that are easier than traditional V0s, and so the V scale does not accurately represent the range of difficulties in our gym. Our boulder circut grading can be found below.

Now that you know the climbing basics – come climb with us!